In the Butchulla language the word means ‘paradise’. Though this 76 x 14 mile island has long been known as Fraser Island, after an 1836 shipwreck survivor, the original language word describes the place much, much better. After all, no one knows who Eliza Fraser is, but anyone can clearly see how beautiful the island is. Few, however, would immediately guess how dangerous it was.

In 1991 an episode of Seinfeld aired in which ‘Maybe the dingo ate your baby’ became an immediate watercooler catch phrase. As with so many things said on that show, it seemed an absurd, out-of-leftfield thing to say in a cartoonish Australian accent, but that show wasn’t alone. In fact there is a whole Wikipedia page devoted to the phrase, in which 21 different pop culture references are listed in which the phrase is repeated in some form. But the real life story behind the phrase was no laughing matter.

It comes from the true life story of a woman named Lindy Chamberlain-Creighton, whose baby vanished from their tent one night while camping near Uluru in the Northern Territory in 1980. She claimed that a dingo had entered their tent and carried away her nine month old baby. But rather than eliciting sympathy and compassion from the authorities, she was instead accused of murdering her child and taken to court. The general public summarily found her guilty of the crime, as did the judge overseeing the trial, and she was imprisoned in 1982. Her family name and reputation were completely destroyed, and as a result of the strain her marriage fell apart. Yet she resolutely continued fighting to prove her innocence.

Then in 1986 a British man fell to his death during a night climb on Uluru. His body was located after an eight day search in an area where many dingo dens were also located. Not far away a baby’s jacket was also found. It was that of little Azaria Chamberlain, and it was confirmation that the mother who had been assumed guilty of infanticide for half a decade was in fact innocent. Her daughter had indeed been carried off by a dingo.

Since then, the savage ferocity of Australia’s wild dogs has been well documented and these animals, once thought incapable of attacking humans, have gained a fearsome reputation.

Now as we made our way around Fraser Island, we were constantly reminded of their presence.

How had it all come to this?

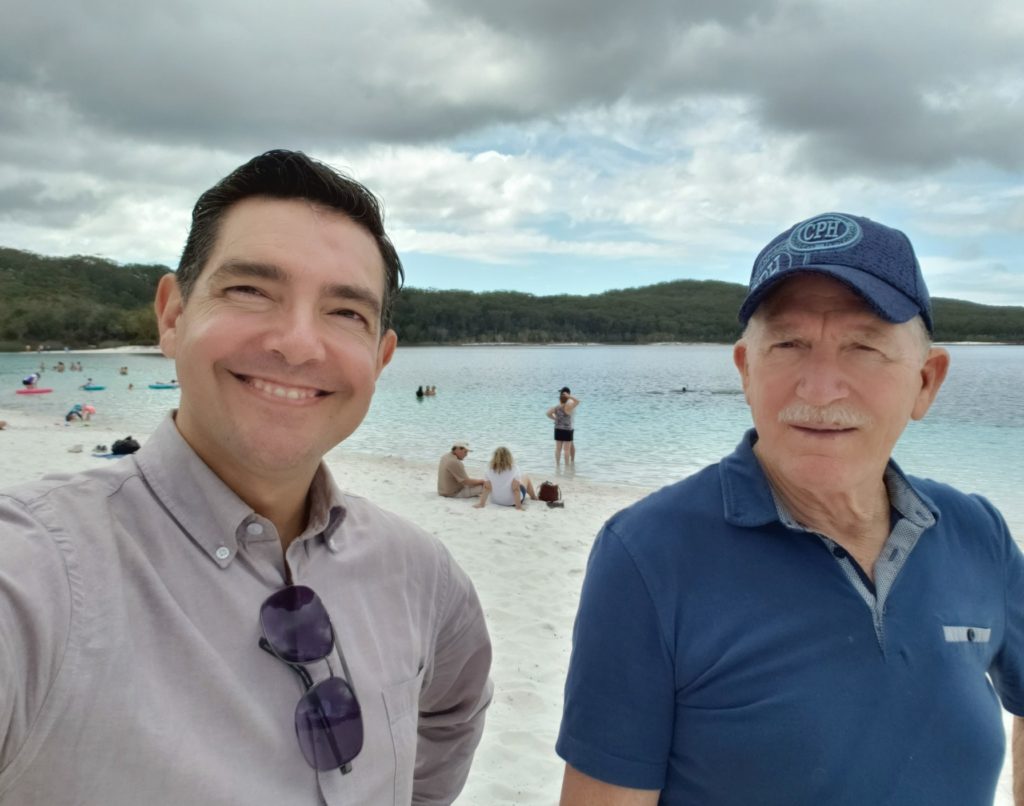

It was fifteen minutes past our designated pick up time that morning as Peter and I stood waiting at the entrance of the caravan park when a long haired woman pulled up in a Land Cruiser to collect us. When it was noted that she had a thick mustache, we realized our mistake. This was our driver. His name was Les Sampson and suddenly the long, flowing locks seemed fitting. Initially I didn’t think I was going to like Les. He started talking and talking and just wouldn’t stop. Bolted to the back of his seat and wrapping around to the side was a homemade, plexi glass shield intended, I guess, to provide a safety barrier from sneezes. We drove into town and stopped to pick up four other people, a family from New Zealand, who would also be coming along. Les drove us past grazing kangaroos to a ferry landing where we loaded up his vehicle and an hour later we drove off the ferry and onto the island. The adventure had begun.

I had had an idea in mind of what Aussie blokes were like before coming to Oz, having based these primarily on men like Steve Irwin and Paul Hogan, but I had met few people who had actually lived up to the image. Until I met Les, that is. He had a jovial ruggedness and seemed to have a limitless number of stories to tell in his thick accent. He held all of our interest for the whole day as he talked about dingos, sharks, albino wallabies, and stupid people from sundry lands. Overall he was just a lot of fun to be with and super down to Earth.

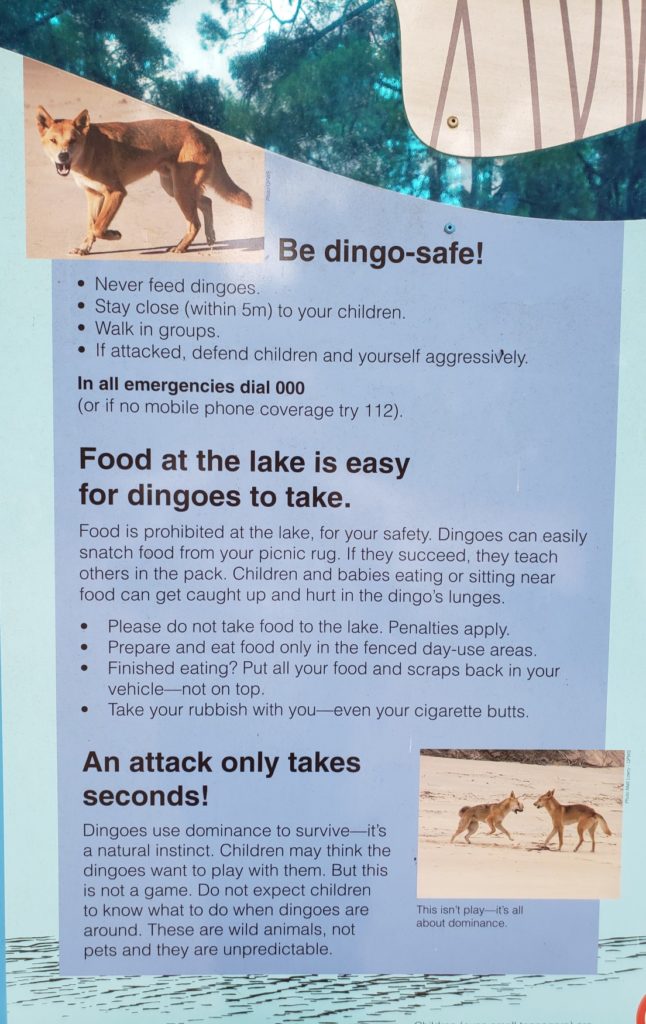

As we drove onto a deeply rutted sand road that crawled over steep hills and through large trenches, constantly threatened to get us stuck, and often brought us within inches of trees, he proclaimed that the roads were ‘in excellent condition for a change’. He also began giving us important training on what to do if we came across a dingo.

Rule one: look it straight in the eye, stand tall, and hold your ground. Rule two: try to get your back against a tree or wall so other dingoes can’t get around behind you. Rule three: never, NEVER run while on the island. This last was very important because it was the running motion that triggered the animals to give chase and attack.

We were told about a man whose young son had run off just a little ways ahead of him and been killed by a pack of dogs before he could do anything to stop it. In another instance a pair of young women who should have known better went for a run by Lake McKenzie one morning and were badly mauled. After one of these attacks, the local dingo population was culled and over 120 animals were killed. Now there are far fewer than there once were, but they still had a healthy presence on the island. But despite the dangers, it is important that the population continue to thrive here, mainly because the dingoes on K’Gari are the purest remaining strain in Australia. That’s why it is so important not to feed them. Les told us about one time having to lay into a couple who had stopped on a road and were tossing food to the dingos in the hopes of getting a good picture. Les had had to explain that now that the dog associated people with food, it would likely have to be put down since it now presented a danger to people. In getting a ‘cute’ tourist picture, this couple had effectively signed the animal’s death warrant.

Australia’s iconic wild dogs actually come from the same family as the Shiba Inus which are such popular pets in Asia. Even though dingos are wild, they can compatibly breed with many other breeds of dog. This makes them especially dangerous since the raw, feral ferocity of a dingo crossed with the intelligence and size of other domesticated breeds can make them extremely intelligent and extremely vicious. As we stopped for morning tea, Les herded us into a caged area where we could eat at our leisure and not worry about run-ins with hungry dogs. We were each given coffee or tea, a macaroon and a slice of cake. Les told several more stories, but honestly it would be impossible to tell them all here. One, however, related to Lake McKenzie, which were about to see.

One time he had had the pleasure of transporting a passenger who was very African, very tall, and very striking with beautiful long, straight black hair. She went for a swim in the lake and returned sometime later looking completely different with no makeup and an enormous, crazy afro. What she hadn’t known was what Les explained to us now: the water in Lake McKenzie was highly acidic. While not dangerous to people, it did mean that any chemicals one might have put in their hair, or might be wearing in the form of sunblock or cosmetics, would be neutralized and dissolve away. The woman in question had spent a great deal of money getting her hair to look just the way she had wanted, but the acidic water and undone all of it and she had had to ride around the rest of the day with hair that was completely unmanageable. He now made sure to warn people before they took a dip.

Peter and I walked down a wooded path past large, visible ‘Dingo Warning’ signs to have a look at the water, which Peter had said was truly a sight. Even though this island was comprised entirely of sand and surrounded by ocean, the water in the lake was fresh, being filled entirely with rain water. It was perfectly paradisaic and invited a swim, but it was also very cold, so despite having brought togs and a towel I opted for a picture instead. Returning to the car we hiked back up the path when a woman went running past us trying to catch up to her friends.

Now I don’t know if everyone had gotten the same warning about the native dogs as we had, but upon returning to the parking lot we were horrified to see two small, naked children come running out of the woods with the parents only emerging a few moments later with the air of serenely oblivious, cud-chewing, pastured cows. Les immediately went over and gave them a stern warning about the very real and very immediate threat to their children. The parents responded by moving only slightly less slowly, seeming mostly bothered to have to disengage from their conversation and be so involved with their kids. The sad thing is they were not alone. Another set of small children were running back and forth between their unseen parents and the bathrooms. Fortunately nothing happened, it would have been horrendous memory for everyone if something had. Not only would the children have been killed, but we would’ve had to have watched it happen and the animals themselves would have been destroyed thanks to the negligence of the adults on hand.

We piled back into the car and Les next took us to a section of rainforest with a raised walking platform, through which flowed a crystal clear stream of sand filtered water. The forest was incredibly lush with huge trees, ferns, and vegetation of all kinds, which was pretty incredible considering that this island had no soil, but was made entirely of sand. The roots of many of the trees were almost as deep as the trees above ground were tall. It was all serenely beautiful except for one small thing: this area apparently also had a huge concentration of venomous Funnel Web Spiders. Along with the Red Back, they were the deadliest arachnids in Australia. Fortunately we saw none. What we did see were more warning signs about dingoes and even a couple of ‘bear boxes’ designed for storing food well away from campers in cages the animals couldn’t get into.

So rather than being hemmed in by trees, it was time to get out into the open. We made for the beach.