I first had the opportunity to learn about World Wars I and II in High School, and my fascination with them has never gone away. It was such a lengthy, all encompassing, and expansive conflict that even to this day untold stories continue to emerge. These range from horrific events such as the firebombing of Dresden, the German Blitz, and the Holocaust, to fascinating accounts about Oskar Schindler, Claus Von Stauffenberg, and The Paperclip scientists. But this trip afforded me the opportunity to learn a new story in a corner of the world I wouldn’t have thought to look for one.

While lounging at the camper’s retreat one day in December, Mikey Stapleton had suggested that it would be worth my while to make the trip to a place called “Kroombit Tops National Park” to see the remains of a World War II bomber known as Beautiful Betsy. Some weeks before I had seen a framed picture of this plane, or what was left of it, hanging in the local library. Sometime later I had again seen it again, intact this time, printed on a bin cover in Newton Street and afterward sought out the fifth scale replica on display outside the Monto Historical Society. But it wasn’t until Rod and Ann Egan one day suggested that they too were interested in seeing the crash site that the groundwork was laid for an actual expedition to the Kroombit.

And so it was that on a Saturday in August two wagons pulled out of the driveway en route to the Boyne Valley and Kroombit Tops. I ended up piling into the Hilux with Peter and his brother-in-law Tim, while the Egans and DeMeurs lead the way in the Prado. Part of what had precipitated this was that Robert and Dinny DeMeur, who were currently staying at the house in a caravan, had expressed an interest in going to have a look. Another reason was the fact that I would be leaving in just over a month and so there was a certain urgency to do it now before time ran out.

Now there is often a chasm between perception and reality, and this trip turned out to be exhibit A in my prosecution of this belief. I had somehow imagined that the trip would take an hour and a half each way and involve driving over gently sloping gravel roads to a spot where we would alight, have a look and a lunch, and then leave. But there are two important rules with regard to such expeditions. One should always (a) research the trip before undertaking it, and (b) build in extra time for the unexpected. I did neither.

For a start, the trip took four and a half hours each way, which was much longer than the hour and a half I had somehow expected. This was due in large part to the extremely rough roads and the need to navigate them slowly. While part of this trip did indeed involve bitumen and then sloping dirt roads, a great deal of it ended up involving a degree of 4x4ing and off-roading that I had never experienced before. And here I must segue briefly into an observation about the difference between American and Aussie vehicles.

Compared to American hardwoods, American beer, and American coffee, the Aussie equivalents are far more robust. (Cutting through a piece of Ironbark is far different from cutting through pine, and I’ve already gone on at length about the coffee.) The people here, too, are quite tough. Tim had once had his hand crushed under a defective horse trailer hitch while the horses were still inside it. He had had to wait while the horses were removed and then sit cradling the remains of his hand for almost three hours as he was driven at speed to the closest hospital. But today you would never know anything had ever happened. He doesn’t complain, doesn’t draw attention to it, and doesn’t let on that anything is different despite the effects of the nerve damage he no doubt deals with daily. I, on the other hand, may at times stay in bed all day because of a mild headache.

The cars here are just another evidence of this extreme contrast. I can recall once seeing an idiot in a Hummer driving up a mound of gravel to show off how robust his vehicle was at a construction worksite. But here this kind of thing was done with a fair amount of regularity, not for show but out of sheer necessity. How most of the SUVs here aren’t constantly in the shop is a wonder. The utes and wagons here do things on a daily basis that would make American cars shriek in horror and curl into the fetal position. Our trek up to Kroombit was to illustrate the toughness of aussie vehicles in an extremely memorable way.

Part of our journey involved vast areas that, while posted as roads leading to the summit, were at the same time paddocks with grazing cows, some of which appeared in unexpected places incongruous with the ideas of herds in open fields. As we proceeded, the slopes that we climbed began to rise at increasingly steep angles and were often covered by large stones and deeply eroded ruts. The practical effect of climbing or descending these in a seated position was a lot, I imagine, like riding a mechanical bull: your body is knocked about at odd angles and in various directions as it constantly angles, lurches, and braces in an attempt to counterbalance. It was crazy. And this kept up for hours on end.

Another thing to deal with was the bull dust. This was a fine powdery dust that at times would obscure the road in front of us completely as we steadily ate the dust of the lead vehicle . This was slightly unnerving given the steepness of the hills just next to the road. It must be said, however, that both Rodney and Tim handled the roads as if they were drained professionals who had driven these tracks with regularity. At times ‘bikies’ would push past us impatiently amid the dust, squeezing very close to our vehicles even though the track was extremely narrow. These people were mounted on motor bikes and usually had swags or packs lashed to the back.

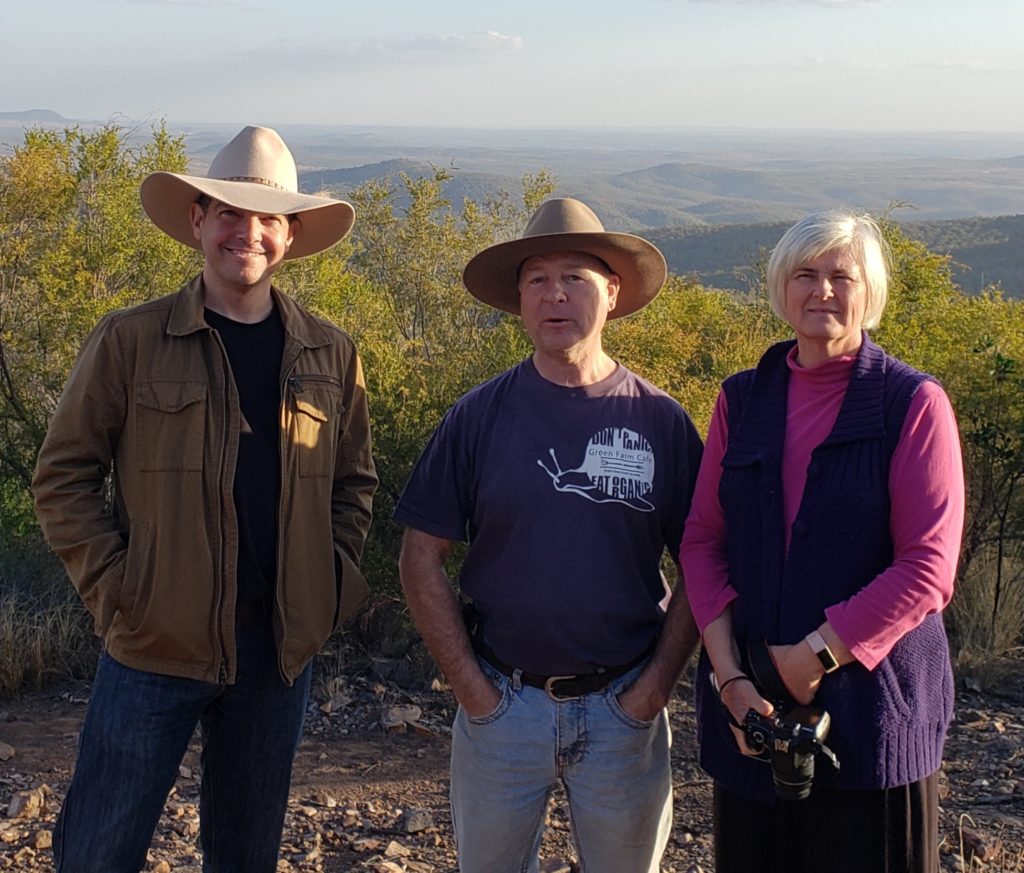

As we passed a notice board with a map, we pulled over to get our bearings. It was only then that the realization of the actual time involved in making this trip really came home to us. We quickly realized what a short way we had come and how far we still had to go: at least two more hours of the same crazy, bumpy, slow-going road just to finish the first stage of the trip. So we charted our course as best we could and just kept moving. We passed the turnoff for an overlook and decided to briefly stop for some pictures. Having done so we pressed stubbornly onward to the crash site.

Some time, we finally arrived at our destination and so parked the cars and began the short hike that lead to the remains of the bomber. The sad story of its untimely demise was told by means of informational plaques set up along a looped walking trail. And so the story unfolded:

On February 26, 1945 an American B-24D Liberator Bomber went missing while flying a ‘fat cat’ mission delivering food and supplies. Though it was known that the plane was flying from Fenton Airfield in the Northern territory to Brisbane, its fate remained a mystery for several decades even though many searches were launched. That the plane was not immediately found is not terribly surprising given that the area to cover was immense and there are huge patches of remote forest that could easily conceal even something as large as a bomber. But then in 1994 a park ranger stumbled across the scattered wreckage of a large aircraft while backburning and the mystery of the plane’s disappearance was finally solved.

Christened Beautiful Betsy after the pilot’s wife, the bomber had crashed on an eminence known as Kroombit Tops. All that remained were scattered pieces of what was once an aircraft and the scant skeletal remains of the eight servicemen who had died with her, which the US Army immediately showed up to recover. The site today serves not only as a final resting place for Betsy but also the eight men who were on board.

Apart from a fairly intact tail section, all that remains are pieces of the wings, four engines, and debris. So great was the impact that parts of the craft have actually been impaled into parts of the engines and pieces of wreckage are scattered over a wide area. Why the plane crashed as it did can only be guessed at, but one theory is that the pilot began a descent after clearing a high peak, believing its path to be clear. They were flying at very low altitude possibly because weather conditions made visibility difficult. At the last minute the pilot saw another mountain just ahead and was only able to lift the nose and open the throttle before the moment of impact. As a result the bomber crashed belly first and was shattered into hundreds of pieces. The men would have died instantly. Tragic, yes, but given the remoteness of the area and the unforgiving environment, any survivors would likely not have escaped with their lives anyways.

Heartbreakingly, one of the British Officers, 23 year old Roy Cannon, was to be married in just four more days, and the other British airman on board, Thomas J Cook, was to have been his Best man in the wedding. Officer Cannon’s final letter home is presented on one of the story placards on the info trail. For those who read the information and let it sink in, it’s a place full of meaning and a good spot for sober introspection. Any place where people have died has a certain gravity to it.

Today the site is treated with a great deal of reverence out of respect for the six American and two British airmen who died there. Amazingly, the pieces of the plane remain in the spots where the landed over fifty years ago instead of having been carted off over the years as souvenirs. It’s an amazing evidence of the respect with which the place is treated.

We had lunch at a camping spot known as “The Wall” before hitting the trail again, choosing to follow a different path on the return trip rather than backtracking, in the hope that it would be faster and/or easier. However The Razorback Track turned out to be just as bad, if not worse, than the road we came up on. We bounced and jostled along for another couple hours through bull dust and deep ruts until we made a brief stop at another overlook. Bbut we we weren’t out of the woods just yet. We encountered a few more minor snags on our way back.

One was the strong smell of something burning at one point. Going downhill at a steep angle it was so necessary to keep a foot on the break, but after a while the brakes themselves began overheating. As a result Tim ended up making generous use of the parking break. Another snag was a large tree limb that had fallen across the path and for which Rod Egan was fortunately prepared, having brought towing straps which made the task of moving something so heavy and ungainly much easier. The third snag came as darkness was beginning to fall and we came to a T junction. We were faced with three possible directions to go, none of which were clearly marked. Choosing the right road was extremely important since trying to navigate such rough hills and trails in the dark would’ve been a nightmare, and all the more so if we had had to turn around after realizing that we had chosen incorrectly. Fortunately a bit more scrutiny of the map revealed the correct way to go, and once we hit Thangool it was a matter of a straight shot down the A3 and we were back to Monto in an hour.

The journey to the top of Kroombit had been far more arduous than what most of us had expected, but fortunately there was no loss of life and it proved to be a truly memorable adventure.

But still more awaited. We had conquered a mountain this weekend. The following week we would head for the ocean.

Great videos! I can’t believe you all undertook that journey! Brave souls…